YOU DON'T HAVE TO BE ON FACEBOOK

You’re shaking your head. Look, I know this is hard for you to understand, but I’m basically Henry Ford here and you are the old carriage driver who’s really worried that I’m going to run over your horse with my new car. And well, yes, I am going to do that — but here’s the thing! We’re doing it together.

All right, I’m still working on that metaphor, but let’s talk about the printing press. You see, when the printing press was invented, people were very afraid of it. They tried to stop it. But the printing press democratized access to information. That’s what we want to do with your information — democratize it — and make it available to every person, everywhere. We want to set your data free!

And we intend to make a fortune doing it.

Source: "Your Privacy Is Our Business" By Jessica Powell - NY Times - 4/27/2019

The article above is of course intended as satire -- SpinShield

AMONG THE MEGA-CORPORATIONS that surveil you, your cellphone carrier has always been one of the keenest monitors, in constant contact with the one small device you keep on you at almost every moment. A confidential Facebook document reviewed by The Intercept shows that the social network courts carriers, along with phone makers — some 100 different companies in 50 countries — by offering the use of even more surveillance data, pulled straight from your smartphone by Facebook itself.

Offered to select Facebook partners, the data includes not just technical information about Facebook members’ devices and use of Wi-Fi and cellular networks, but also their past locations, interests, and even their social groups. This data is sourced not just from the company’s main iOS and Android apps, but from Instagram and Messenger as well. The data has been used by Facebook partners to assess their standing against competitors, including customers lost to and won from them, but also for more controversial uses like racially targeted ads.

Facebook’s cellphone partnerships are particularly worrisome because of the extensive surveillance powers already enjoyed by carriers like AT&T and T-Mobile: Just as your internet service provider is capable of watching the data that bounces between your home and the wider world, telecommunications companies have a privileged vantage point from which they can glean a great deal of information about how, when, and where you’re using your phone. AT&T, for example, states plainly in its privacy policy that it collects and stores information “about the websites you visit and the mobile applications you use on our networks.” Paired with carriers’ calling and texting oversight, that accounts for just about everything you’d do on your smartphone.

{A} confidential Facebook document provides an overview of Actionable Insights and espouses its benefits to potential corporate users. It shows how the program, ostensibly created to help improve underserved cellular customers, is pulling in far more data than how many bars you’re getting. According to one portion of the presentation, the Facebook mobile app harvests and packages eight different categories of information for use by over 100 different telecom companies in over 50 different countries around the world, including usage data from the phones of children as young as 13. These categories include use of video, demographics, location, use of Wi-Fi and cellular networks, personal interests, device information, and friend homophily, an academic term of art. . . “the tendency of nodes to form relations with those who are similar to themselves.” In other words, Facebook is using your phone to not only provide behavioral data about you to cellphone carriers, but about your friends as well.

{A}rmed with location data beamed straight from your phone, Facebook could technically provide customer location accurate to a range of several meters, indoors or out.

Joel Reidenberg, a professor and director of Fordham’s Center on Law and Information Policy, Facebook’s credit-screening business seems to inhabit a fuzzy nether zone with regards to the FCRA, neither matching the legal definition of a credit agency nor falling outside the activities the law was meant to regulate. “It sure smells like the prescreening provisions of the FCRA,” Reidenberg told The Intercept.

Reidenberg also doubted whether Facebook would be exempt from regulatory scrutiny if it’s providing data to a third party that’s later indirectly used to exclude people based on their credit, rather than doing the credit score crunching itself, ŕ la Equifax or Experian. “If Facebook is providing a consumer’s data to be used for the purposes of credit screening by the third party, Facebook would be a credit reporting agency,” Reidenberg explained. “The [FCRA] statute applies when the data ‘is used or expected to be used or collected in whole or in part for the purpose of serving as a factor in establishing the consumer’s eligibility for … credit.'” If Facebook is providing data about you and your friends that eventually ends up in a corporate credit screening operation, “It’s no different from Equifax providing the data to Chase to determine whether or not to issue a credit card to the consumer,” according to Reidenberg.

Chris Hoofnagle, a privacy scholar at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, told The Intercept that this sort of consumer rating scheme has worrying implications for matters far wider than whether T-Mobile et al. will sell you a discounted phone. For those concerned with their credit score, the path to virtue has always been a matter of commonsense personal finance savvy. The jump from conventional wisdom like “pay your bills on time” to completely inscrutable calculations based on Facebook’s observation of your smartphone usage and “friend homophily” isn’t exactly intuitive.

Source: "THANKS TO FACEBOOK, YOUR CELLPHONE COMPANY IS WATCHING YOU MORE CLOSELY THAN EVER" Sam Biddle - The Intercept - May 20 2019

Google and Facebook have become the dominant forces in online advertising, gobbling up information as their users move around their platforms and the internet at large. But their aggressive collection of user data — laid bare by several embarrassing scandals in recent years — has put the companies in the cross hairs of politicians and global regulators.

Google separately announced it would take steps to limit the use of tracking cookies on Chrome, the world’s most popular browser with about a 60 percent market share.

Cookies allow companies to monitor which websites people visit and what ads they have viewed or clicked on.

The internet giant { . . . } already knows more valuable information such as what users search for, what videos they watch and what apps they’ve loaded on their phones.

Source: "Google Says It Has Found Religion on Privacy" By Daisuke Wakabayashi and Brian X. Chen - NY Times May 7, 2019 Image

Today’s data providers can receive information from almost every imaginable part of your life: your activity on the internet, the places you visit, the stores you walk through, the things you buy, the things you like, who your friends are, the places your friends go, the things your friends do, and on and on. One provider boasts about having “precise second-by-second viewing of tens of millions of televisions in all 210 local markets across the country.” If you responded to an online event invitation, the details could be used to target you. If you’re listening to energetic music, you could be targeted almost instantly in an energetic mood group. Much of this data could be shared among brands.

You might find targeted ads preferable to general ones since there’s a better chance that you might actually want to buy the products being marketed. But privacy advocates say targeting has gotten out of control.

“Do you really need to track people on all the websites they visit, every single app they use, on their entire platform, and keep the data for a shockingly long time?” asked Ms. Kaltheuner, from Privacy International. “Is all of this really necessary to show relevant ads?”

Just by browsing the web, you’re sending valuable data to trackers and ad platforms. Websites can also provide marketers specific things they know about you, like your date of birth or email address.

Ad companies often identify you when you load a website using trackers and cookies — small files containing information about you. Then your data is shared with multiple advertisers who bid to fill the ad space. The winning bid gets to fill the ad slot.

All of this happens in milliseconds.

{O}ur information is used not just to target us but to manipulate others for economic and political ends — invisibly, and in ways that are difficult to scrutinize or even question. And it’s a warning sign about the real-world political risks that come from this sophisticated guessing game, which is played in billions of transactions each day.

“The way ads are targeted today is radically different from the way it was done 10 or 15 years ago,” said Frederike Kaltheuner, who heads the corporate exploitation program at Privacy International. “It’s become exponentially more invasive, and most people are completely unaware of what kinds of data feeds into the targeting.”

Targeted advertising was once limited to simple contextual cues: visiting ESPN probably meant you’d see an ad for Nike. But advertising services today use narrow categories drawn from a mind-boggling number of sources to single out consumers

“In the next election, I think it is inevitable that every single voter will have been profiled based on what they have been reading, watching and listening to for years online,” said Johnny Ryan, the chief policy officer at Brave, a private web browser that allows users to block ads and trackers.

“Surveillance companies are learning to nudge, coax, tune and herd human behavior in the direction that they want people to go for the sake of the commercial outcomes that their business customers seek,” said Shoshana Zuboff, a researcher and author of “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.”

The accuracy of predictions made by data providers is difficult to verify. The companies release little evidence that those included in these groups actually belong there. A study from 2018 found that the gender assigned by data brokers was accurate, on average, only 42 percent of the time – that’s worse than just flipping a coin. So in the ads we bought, we expected many men would see ads aimed at women and vice versa.

Data providers also say the information stored and shared is anonymous, but that doesn’t mean it stays that way. In 2017, for example, German researchers tied data that was supposedly anonymous back to specific individuals. They found revealing things like the medication used by a German politician and a German judge’s use of pornography.

Ms. Zuboff, the author and researcher, argues that companies today are mining private lives the same way they exploit natural resources, turning them into profitable goods. She said that makes every “smart” device and “personalized” service just another way to collect data for the surveillance economy.

That change happened so quickly and so secretly, Ms. Zuboff argues, that the public is not equipped to fight back.

Ms. Kaltheuner agreed. “It’s about ads, but it has all these other implications that have nothing to do with ads,” she said. “And that’s the price we’re paying to see ‘relevant’ ads.”

Source: "These Ads Think They Know You" By Stuart A. Thompson - NY Times - 4/30/2019

Facebook has filed thousands of patent applications since it went public in 2012. One of them describes using forward-facing cameras to analyze your expressions and detect whether you’re bored or surprised by what you see on your feed. Another contemplates using your phone’s microphone to determine which TV show you’re watching. Others imagine systems to guess whether you’re getting married soon, predict your socioeconomic status and track how much you’re sleeping.

A review of hundreds of Facebook’s patent applications reveals that the company has considered tracking almost every aspect of its users’ lives: where you are, who you spend time with, whether you’re in a romantic relationship, which brands and politicians you’re talking about. The company has even attempted to patent a method for predicting when your friends will die.

Taken together, Facebook’s patents show a commitment to collecting personal information, despite widespread public criticism of the company’s privacy policies and a promise from its chief executive to “do better.”

Reading your relationships

One patent application discusses predicting whether you’re in a romantic relationship using information such as how many times you visit another user’s page, the number of people in your profile picture and the percentage of your friends of a different gender.

Predicting your future

This patent application describes using your posts and messages, in addition to your credit card transactions and location, to predict when a major life event, such as a birth, death or graduation, is likely to occur.

Identifying your camera

Another considers analyzing pictures to create a unique camera “signature” using faulty pixels or lens scratches. That signature could be used to figure out that you know someone who uploads pictures taken on your device, even if you weren’t previously connected. Or it might be used to guess the “affinity” between you and a friend based on how frequently you use the same camera.

Listening to your environment

This patent application explores using your phone microphone to identify the television shows you watched and whether ads were muted. It also proposes using the electrical interference pattern created by your television power cable to guess which show is playing.

Tracking your routine

Another patent application discusses tracking your weekly routine and sending notifications to other users of deviations from the routine. In addition, it describes using your phone’s location in the middle of the night to establish where you live.

Inferring your habits

This patent proposes correlating the location of your phone to locations of your friends’ phones to deduce whom you socialize with most often. It also proposes monitoring when your phone is stationary to track how many hours you sleep.

As long as Facebook keeps collecting personal information, we should be wary that it could be used for purposes more insidious than targeted advertising, including swaying elections or manipulating users’ emotions, said Jennifer King, the director of consumer privacy at the Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School. “There could be real consequences,” she said.

That isn’t likely to change, said Siva Vaidhyanathan, a professor of media studies at the University of Virginia. “I’ve seen no indication that Facebook has changed its commitment to watch everything we do, record everything we do and exploit everything we do,” he said.

Source: "7 Creepy Patents Reveal About Facebook" By Sahil Chinoy - NY Times - 7/13/18

“The popular ones are designed for behavior modification. It’s like, why would you go sign up for an evil hypnotist who’s explicitly saying that his whole purpose is to get you to do things that people have paid him to get you to do, but he won’t tell you who they are?” --Jaron Lanier

Mr. Lanier believes that Facebook and Google, with their “top-down control schemes,” should be called “Behavior Modification Empires.”

“The Facebook business model is mass behavior modification for pay. And for those who are not giving Facebook money, the only — and I want to emphasize, the only, underlined and in bold and italics — reward they can get or positive feedback is just getting attention. And if you have a system where the only possible prize is getting more attention, then you call that system Christmas for Asses, right? It’s a creep-amplification device.

“Once Facebook becomes ubiquitous, it’s a sort of giant protection racket, where, if you don’t pay them money, then someone else will pay to modify the behavior to your disadvantage, so everyone has to pay money just to stay at equilibrium where they would have been otherwise,” he says. “I mean, there’s only one way out for Facebook, which is to change its business model. Unless Facebook changes, we’ll just have to trust Facebook for any future election result. Because they do apparently have the ability to change them. Or at least change the close ones.”

Why would Facebook change its business model when it’s raking in billions?

“I would appeal to the decency of the people in it,” he replies. “And if not to them, then the toughness of the regulators. It’s going to be one of the struggles of the century.”

I point out that after the stunning Trump win, President Obama took Mr. Zuckerberg aside and warned him to take the threat of political disinformation seriously, but the young billionaire dismissed the idea that it was widespread.

“Well, no one in Silicon Valley believes that anybody knows more than us,” Mr. Lanier says dryly. “Surely not the government.”

He continues: “I think there are a lot of good people at Facebook, and I don’t think they’re evil as individuals. Or at least not the ones that I’ve met. And I know Google a lot better, and I feel pretty certain that they’re not evil. But both of these companies have this behavior-manipulation business plan, which is just not something the world can sustain at that scale. It just makes everything crazy.”

“People in the community knew,” Mr. Lanier says, adding that he wrote essays and participated in debates in the early 1990s about how easy it would be the create unreality and manipulate society, how you could put out a feed of information that would put people in illusory worlds where they thought they had sought out the information but actually they had been guided “the way a magician forces a card.”

“So for somebody to say they didn’t know the algorithms could do that,” Mr. Lanier says in a disbelieving tone. “If somebody didn’t know, they should’ve known.”

So what happens when fake news marries virtual reality?

“It could be much more significant,” Mr. Lanier says. “When you look at all the ways of manipulating people that you can do with just a crude thing like a Facebook feed — when people are just looking at images and text on their phones and they’re not really inside synthetic worlds yet — when you can do it with virtual reality, it’s like total control of the person. So what I’m hoping is that we’re going to figure this stuff out so we don’t make ourselves insane before virtual reality becomes mature.”

He says that Silicon Valley has turned out both better and worse than he expected: “As far as the worse part, creating a global behavior-modification empire is worse than I thought. And creating a world that’s more opaque instead of less opaque is worse than I thought we should do. It’s also a physically uglier place than I thought it would be. It’s really a shame. If we’re the new Renaissance, why don’t we make this amazing Tuscany here? We have these gorgeous orchards. Why don’t we do something beautiful here instead of just filling it up with parking lots and horrible buildings?”

Source: "Soothsayer in the Hills Sees Silicon Valley’s Sinister Side" By Maureen Dowd - NY Times - Nov. 8, 2017

After Facebook helped spread misinformation during the 2016 presidential campaign, company executives vowed to do better. They put in place policies meant to reduce the amount of political misinformation on the platform.

They’re not doing a very good job of keeping their word.

Judd Legum, author of the Popular Information newsletter, wrote yesterday that he had “identified hundreds of ads from the Trump [2020 re-election] campaign that violated Facebook’s ad policies. Facebook removed the ads only after I brought them to its attention.”

Legum discovered Team Trump again using dirty tricks. This time, it has falsely put the same quotation in the mouths of two different African-American men portrayed in different ads, one old and one young: “Sir, you have really inspired me and brought back my faith in this great nation. From the bottom of my heart, thank you for all the work you are doing.”

And Media Matters, a liberal watchdog group, wrote the following in response to Legum’s new reporting:

“This isn’t the first time Facebook has failed to detect policy violations by advertisers on the platform. In September, Media Matters found a series of ads from right-wing clickbait sites, conspiracy theorists, and extremists which violated Facebook’s policies on false content and discriminatory practices. These ads included: posts from white supremacist Paul Nehlen promoting another white supremacist; anti-Muslim false news; anti-LGBT content; and 9/11 truther, QAnon, and Pizzagate conspiracy theories.”

The central problem seems to be that Facebook is primarily using an artificial-intelligence algorithm to police ads — and the algorithm isn’t very effective.

“Facebook,” he added, “is asleep at the wheel.”

Facebook is a powerful force in society today, and with that power comes responsibility. The company needs to do better.

Source: "Facebook, ‘Asleep at the Wheel’" By David Leonhardt - NY Times - April 30, 2019

Facebook announced late last month {September 2018} the biggest data breach in its history, affecting nearly 50 million user accounts. In the same week, the news site Gizmodo published an investigation that found Facebook gave advertisers contact information harvested from the address books on their users’ cellphones.

Equally worrisome from Gizmodo’s report: Facebook is also giving advertisers phone numbers that users have provided solely for security reasons. Security experts generally advise users to add two-factor authentication to their accounts, which sometimes takes the form of providing a phone number to receive text messages containing log-in codes. It’s ironic — two-factor authentication is supposed to better safeguard privacy and security, but these phone numbers are winding up in the hands of advertisers.

(In the meantime, falsehoods about Judge Kavanaugh’s accuser Christine Blasey Ford are going viral on Facebook).

Source: "Did Facebook Learn Anything From the Cambridge Analytica Debacle?" - NY Times - 10/6/2018

Facebook on Friday offered a bit of ... news about the massive data breach that it first revealed Sept. 28 {2018}

The bad news is Facebook can now confirm that the vast majority of those victims did indeed have their personal information stolen. (All it had said previously was that their accounts were accessed.)

Of the 30 million affected, . . . 15 million had basic personal information stolen, such as their name and contact information. That’s bad, especially if the contact information included people’s cellphone numbers—and doubly so if they were using those cellphone numbers for two-factor authentication, a key security measure in many online services.

But what’s really bad is that a much richer set of personal data was stolen from 14 million Facebook users. In a blog post, Facebook said that data included the following:

Username, gender, locale/language, relationship status, religion, hometown, self-reported current city, birthdate, device types used to access Facebook, education, work, the last 10 places they checked into or were tagged in, website, people or Pages they follow, and the 15 most recent searches.

Yikes! That’s the kind of information that could be used to stalk someone, to harass them or their family, to answer the security questions that guard their online accounts, to deceive them by posing as someone they know, or to trick them into clicking a malicious link or disclosing sensitive information. Those are just a handful of the possibilities that leap to mind.

Source: "The Facebook Hack Could Haunt Its Victims for Years to Come" By Will Oremus - Slate - Oct 12, 2018•

A 12-year-old transgender student in a small Oklahoma town near the Texas border was targeted in an inflammatory social media post by the parents of a classmate, leading to violent threats and driving officials to close the school for two days.

It all started on Facebook.

Source: "Transgender Girl, 12, Is Violently Threatened After Facebook Post by Classmate’s Parent" By Christina Caron - NY Times - Aug. 15, 2018

{T}he United States, unlike some countries, has no single, comprehensive law regulating the collection and use of personal data. The rules that did exist were largely established by the very companies that most relied on your data, in privacy policies and end-user agreements most people never actually read. {T}here {is} no real limit on the information companies could collect or buy about {you} — and that just about everything they could collect or buy, they did. They knew things like {your} shoe size, of course, and where {you live}, but also roughly how much money {you} made, and whether {you are} in the market for a new car. With the spread of smartphones and health apps, they could also track {your} movements or whether {you have} gotten a good night’s sleep. Once facial-recognition technology was widely adopted, they would be able to track {you} even if {you} never turned on a smartphone.

All of this . . . was designed to help the real customers — advertisers — sell {you} things. Advertisers and their partners in Silicon Valley were collecting, selling or trading every quantum of {yourself} that could be conveyed through the click of a mouse or the contents of {your} online shopping carts. They knew if {you} had driven past that Nike billboard before finally buying those Air Force 1s. A website might quote {you} a higher price for a hair dryer if {you} lived in a particular neighborhood, or less if {you} lived near a competitor’s store. Advertisers could buy thousands of data points on virtually every adult in America. With Silicon Valley’s help, they could make increasingly precise guesses about what you wanted, what you feared and what you might do next: Quit your job, for example, or have an affair, or get a divorce.

And no one knew more about what people did or were going to do than Facebook and Google, whose free social and search products provided each company with enormous repositories of intimate personal data. They knew what you “liked” and who your friends were. They knew not just what you typed into the search bar late on a Friday night but also what you started to type and then thought better of. Facebook and Google were following people around the rest of the internet too, using an elaborate and invisible network of browsing bugs — they had, within little more than a decade, created a private surveillance apparatus of extraordinary reach and sophistication.

To Silicon Valley, personal information had become a kind of limitless natural deposit, formed in the digital ether by ordinary people as they browsed, used apps and messaged their friends. Like the oil barons before them, they had collected and refined that resource to build some of the most valuable companies in the world, including Facebook and Google, an emerging duopoly that today controls more than half of the worldwide market in online advertising. But the entire business model — what the philosopher and business theorist Shoshana Zuboff calls “surveillance capitalism” — rests on untrammeled access to your personal data. The tech industry didn’t want to give up its powers of surveillance. It wanted to entrench them.

By last year {2017}, Google’s parent, Alphabet, was spending more money on lobbyists than any other corporation in America.

Facebook. . . became one of the world’s biggest collectors of personal data and a powerful presence in Washington and beyond. It acquired Instagram, a rival social media platform, and the messaging service WhatsApp, bringing Facebook access to billions of photos and other user data, much of it from smartphones; formed partnerships with country’s leading third-party data brokers, such as Acxiom, to ingest huge quantities of commercial data; and began tracking what its users did on other websites. Smart exploitation of all that data allowed Facebook to target advertising better than almost anyone, and by 2015, the company was earning $4 billion a year from mobile advertising. Starting in 2011, Facebook doubled the amount of money it spent on lobbying in Washington, then doubled it again.

Last year {2017}, at least five other states considered passing legislation regulating the commercial use of biometrics. Only one, Washington, actually passed a law — and it includes precisely the loophole that tech interests sought to carve out in Illinois, excluding “a physical or digital photograph, video or audio recording or data generated therefrom.” The exception covers facial scans and even voiceprints — the kind of technology that Amazon, based in Washington, uses to power Alexa, the virtual assistant that has a microphone in millions of American homes.

The Times and The Observer of London revealed that a contractor for {a political analytics firm called Cambridge Analytica} had harvested private information from more than 50 million Facebook users, exploiting the social-media activity of a huge swath of the American electorate and potentially violating United States election laws. Within weeks, Facebook acknowledged that as many as 87 million users might have been affected, marking one of the biggest known data leaks in the company’s history.

{Mark}Zuckerberg’s company {Facebook} was . . . financing a campaign {the Committee to Protect California Jobs} to stop new privacy regulations in California.

Facebook . . . had developed a legislative counterproposal . . . It was vague about data collected from mobile phones, and it appeared to exclude Facebook’s own network of “like” and “share” buttons around the Web, one of the company’s chief means of tracking consumers when they weren’t on Facebook. And while it limited the sale of data, it seemed to allow companies to make deals to swap data back and forth, potentially a major loophole.

Source: "The Unlikely Activists Who Took On Silicon Valley — and Won" by Nicholas Confessore - NY Times - Aug. 14, 2018

Time and again, communal hatreds overrun the newsfeed — the primary portal for news and information for many users — unchecked as local media are displaced by Facebook and governments find themselves with little leverage over the company. Some users, energized by hate speech and misinformation, plot real-world attacks.

A reconstruction of Sri Lanka’s descent into violence, based on interviews with officials, victims and ordinary users caught up in online anger, found that Facebook’s newsfeed played a central role in nearly every step from rumor to killing.

{T}he imagined Ampara, which exists in rumors and memes on Sinhalese-speaking Facebook, is the shadowy epicenter of a Muslim plot to sterilize and destroy Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese majority.

{W}here institutions are weak or undeveloped, Facebook’s newsfeed can inadvertently amplify dangerous tendencies. Designed to maximize user time on site, it promotes whatever wins the most attention. Posts that tap into negative, primal emotions like anger or fear, studies have found, produce the highest engagement, and so proliferate.

In the Western countries for which Facebook was designed, this leads to online arguments, angry identity politics and polarization. But in developing countries, Facebook is often perceived as synonymous with the internet and reputable sources are scarce, allowing emotionally charged rumors to run rampant. Shared among trusted friends and family members, they can become conventional wisdom.

And where people do not feel they can rely on the police or courts to keep them safe, research shows, panic over a perceived threat can lead some to take matters into their own hands — to lynch.

Last year, in rural Indonesia, rumors spread on Facebook and WhatsApp, a Facebook-owned messaging tool, that gangs were kidnapping local children and selling their organs. Some messages included photos of dismembered bodies or fake police fliers. Almost immediately, locals in nine villages lynched outsiders they suspected of coming for their children.

Near-identical social media rumors have also led to attacks in India and Mexico. Lynchings are increasingly filmed and posted back to Facebook, where they go viral as grisly tutorials.

Facebook’s most consequential impact may be in amplifying the universal tendency toward tribalism. Posts dividing the world into “us” and “them” rise naturally, tapping into users’ desire to belong.

Its gamelike interface rewards engagement, delivering a dopamine boost when users accrue likes and responses, training users to indulge behaviors that win affirmation.

And because its algorithm unintentionally privileges negativity, the greatest rush comes by attacking outsiders: The other sports team. The other political party. The ethnic minority.

Online outrage mobs will be familiar to any social media user. But in places with histories of vigilantism, they can work themselves up to real-world attacks. Last year in Cancún, Mexico, for instance, Facebook arguments over racist videos escalated to fatal mob violence.

Source: "Where Countries Are Tinderboxes and Facebook Is a Match" By AMANDA TAUB and MAX FISHER - NY Times - APRIL 21, 2018

Not long ago, debates about privacy and surveillance were theoretical.

Those of us who pushed for stronger protections from surveillance have often invoked hypothetical situations in which oppressive states use private data to profile and target undesirable populations or individuals.

We no longer need to conjure hypotheticals. On June 29, Facebook revealed to congressional investigators that it granted Mail.ru, a Russian internet company with close ties to the Kremlin, a special extension of the Facebook policy that allowed thousands of application developers access to massive amounts of user data.

Mail.ru ran applications on Facebook for years before 2015, allowing it to delve into Facebook profiles and activity from millions of users around the world. This was standard Facebook policy. Thousands of companies that built applications on the Facebook platform had access to potentially millions of users’ information.

Mark Zuckerberg had told Congress in April that it ended this policy of massive data sharing in May 2015. But in its 748-page response to questions from the House Energy and Commerce Committee, the company admitted that it had granted a handful of companies permission to continue to have access to that data for six extra months. Mail.ru was on the list of companies granted this favor.

Facebook has not released the full list of thousands of companies around the world that had similar, almost complete, access to our likes and desires for years. The public might never know how many of these companies were connected to other dangerous and destructive forces in the world.

Any oppressive state seeking to monitor troublesome elements of its population — such as gay-rights groups, religious minorities, political critics or human-rights workers — could use such front companies to collect Facebook information on critics and stifle dissent. Nationalist leaders like Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Narendra Modi in India and Uhuru Kenyatta in Kenya use Facebook to spread propaganda and derogatory information about opponents and critics. Having access to extensive personal Facebook data on citizens could make such leaders more dangerous.

Facebook has no idea how much personal data it let companies have or how far it might have traveled. It might never know. And neither will we.

The process of holding Facebook to account will take many years. But the debate over privacy and surveillance is no longer about “what ifs.” Facebook has already made us vulnerable to abuses by hostile forces around the world. Responsible, accountable governments must do more to protect us.

Source: "This Russian Company Knows What You Like on Facebook" By Siva Vaidhyanathan - NY Times - July 12, 2018

David Carroll, a professor at the New School, who took legal action against Cambridge Analytica in the United Kingdom, agreed that, “no fine would be adequate for a monopoly. Advertisers, users, and investors do not register the fines in their economic activity. [They’re] still buying, using investing. It causes no material harm to Facebook. It’s just bad PR.”

What does he have in mind? “Seizure of servers, criminal penalties against corporate directors and Stop Data Processing orders would actually be painful penalties,” he argued. Or, even more intense, “force Facebook to delete its user data and models and start from scratch under rigorous collection restrictions."

Of course, Facebook is not likely to see anything resembling Mr. Carroll’s proposals anytime soon; most ideas would likely be dismissed as wildly radical. And certainly without precedent.

And yet the scope of Facebook’s recent privacy scandals in the last two years has little precedent either. A quick, partial rundown:

- A security flaw that potentially exposed the public and private photos of as many as 6.8 million users on its platform to developers (the company told the told European regulators almost two months after discovering the bug and waited almost three months before disclosing publicly).

- A separate “bug” that exposed up to 30 million users’ personal information in late September. Among the information exposed: emails and phone numbers, and profile information including recent search history, gender and location.

- An admission that the company "unintentionally uploaded" the email contacts of 1.5 million new Facebook users since May 2016.

- And, of course, the Cambridge Analytica scandal, where data from tens of millions of users was misappropriated and shared to be used for profiling for political campaigning

Source: "How Do You Stop Facebook When $5 Billion Is Chump Change?" By Charlie Warzel - NY Times - 4/26/2019

How can I describe the fine of between $3 billion and $5 billion that Facebook is likely to pay to the Federal Trade Commission{?} {T}hey’re going to need a bigger fine if they actually want to stop Facebook from violating its users’ privacy.

Back in 2011, with I’m-sorrys all around, Facebook signed a consent decree with the F.T.C. around a different set of data abuse issues. This new fine presumably will cover all of the fresh I’m-sorrys since then, for the various and sundry violations that the company has committed over the last several years, including the mistakes the company made in not seeing and then not quickly plugging the epic Cambridge Analytica data leak.

Source: "Put Another Zero on Facebook’s Fine. Then We Can Talk." By Kara Swisher - NY Times - 4/26/2019

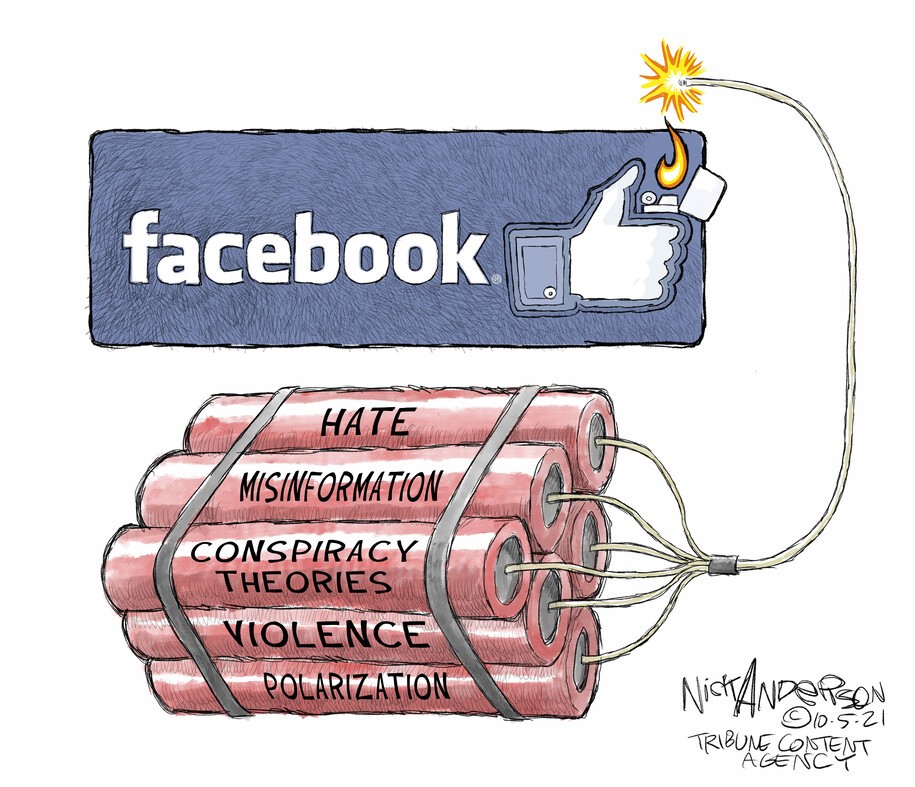

Source: Nick Anderson - Tribune Content Agency